Mushrooms are fascinating. They take thousands of shapes. They can nourish or poison, harm as readily as they heal. They can take your meal to the next level or your mind to another plane. They’re elusive and mysterious, growing in strange places under weird conditions. There’s a lot packed into these strange little creatures. Naturally, they’ve inspired humans as long as we’ve known about them, appearing often in art and stories across cultures.

To celebrate this, we’re launching a series on the role mushrooms have played in the work of renowned artists. First up, we’re highlighting one of the most popular artists working today, Japan’s Takashi Murakami.

Murakami began his career with a robust arts education, earning a BFA in Japanese painting at the Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music in 1986, where he returned for his PhD in 1993.

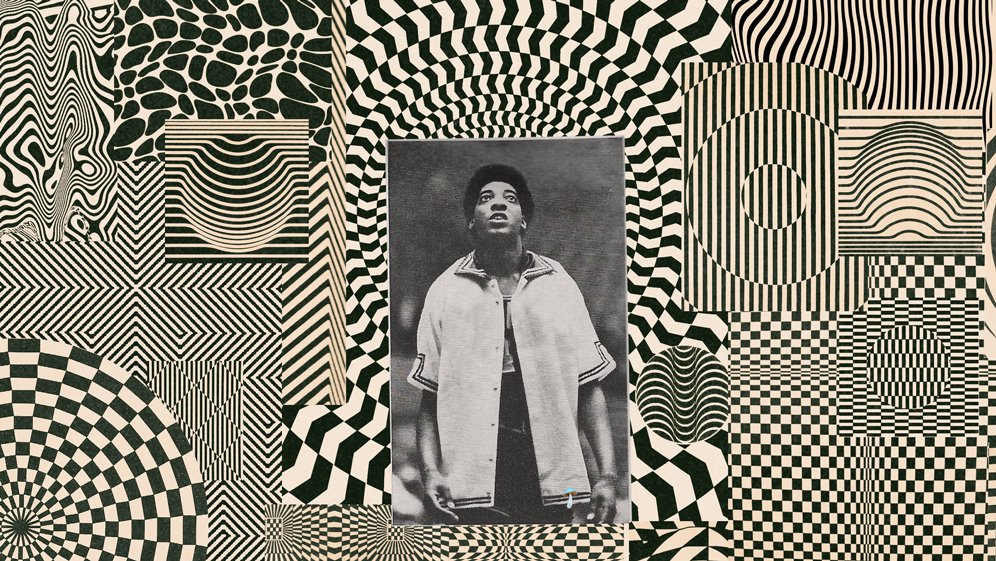

Soon thereafter he began developing a signature mash-up style that combines traditional Japanese painting with contemporary pop art. He called it “Superflat,” an apt summation of the way he renders images in a flattened two dimensions, as opposed to Western art’s subscription to a more-lifelike three dimensions.

Putting the “fun” in fungi

In 1999 Murakami created the first of his notable mushroom pieces, a painting entitled Super Nova. It shows a line-up of wide-eyed, cartoonish mushroom figures in psychedelic patterns and a technicolour palette. With every aspect layered on the same visual plane, it’s a classic example of Murakami’s Superflat style. The subject matter acknowledges his country’s ancient interest in mushrooms, while the vivid palette, cartoon aesthetic, and trippy patterns evoke the potent effects of psilocybin, one of the most mysterious of this special plant’s many facets.

Murakami’s interest in fungi places him in a rich lineage of Japanese artists. Itō Jakuchū, the 18th century painter, often featured mushrooms in his beautiful and detailed images of fauna and flora, particularly his 1761 piece Compendium of Vegetables and Insects, which could be seen as a direct inspiration for Murakami’s Super Nova over two centuries later. Takehisa Yumeji would similarly feature mushrooms heavily in his paintings and textile designs in the early 20th century.

A cloud comes over mushrooms

The blithe association of mushrooms in Japanese culture changed after the 1945 bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Both the instantaneous devastation inflicted by those mushroom clouds, as well as the decades of deadly and corrupting radiation following their fallout, added a traumatic undertone to the national correlation with mushrooms. New associations of mutation and toxicity joined the lexicon.

This complexity shows up every time Murakami paints mushrooms. His 2002 follow up to Super Nova, an acrylic painting called Army of Mushrooms, is again a sort of catalogue of anime-influenced mushroom characters that combines the ancient Japanese reverence for fungi with modern Japanese pop culture, including subtly dark nuances.

At first Army’s collection of cartoony anthropomorphized mushrooms seem to hew closely to the Japanese notion of Kawaii, characters that are childlike and hyper-cute. The catalogue-style layout of figures evokes Gashapon, the tiny collectible figurines sold in vending machines throughout Japan. Looking closer, however, brings into focus creepy details: numerous unblinking eyes; wiggling, tendril-like stalks; jagged fangs. The psychedelic nature of psilocybin mushrooms arises with the vivid colours and trippy patterns, not to mention the alien and otherworldly forms of the mushrooms themselves, with their heavily-lidded, drowsy eyes and playfully spaced-out expressions.

Murakami struck this theme again in 2007 with Posi Mushroom, another painting that collects a group of mushroom characters mashing together an ancient Japanese theme with modern twists of anime, Kawaii, and psychedelia. “For me,” Murakami has said, “mushrooms seem both erotic and cute while evoking, especially for the Western imagination, the fantastic world of fairy tales.”

Given the thematic richness of a subject so varied and mysterious, no doubt we’ll see more mushrooms in Murakami’s future.